Kristallnacht, or simply Pogromnacht, occurred 80 years ago on November 9-10, 1938. The Pogrom was…

How Many Lives is the Economy Worth: People vs Profits?

The coronavirus pandemic forces our leaders to consider public health choices with serious economic and political consequences. At the core of this decision is a challenging cost-benefit analysis: How many lives is an economy worth?

Beware of Selection Bias

All good analysis requires a sound methodology and reliable data. Due to scant testing, there remains uncertainty about the risk of dying from Covid-19. As of March 26, the reported global case fatality rate (CFR) is 4.5% (here). It is difficult to use this number to fully inform a policy recommendation because the patients who have been tested for SARS Cov-2 are disproportionately those with severe symptoms and bad outcomes.

Because most health systems not only have limited testing capacity, but also limited beds and medical supplies, this initial selection bias is likely to further distort the significance of the CFR. When only the most severe cases are tested and those severe cases cannot be adequately treated, of course there will be high fatalities.

The Diamond Princess cruise ship had a case fatality rate of 1.0%. There were seven deaths out of 696 infected passengers and crew out of a total of 3,711 total people on board. What remains unclear is:

· what was the exact age breakdown of the infected population although the reports suggest that the cruisers were largely an elderly population;

· what infected passengers died later, if any;

· how the frequency of the passengers’ chronic diseases differs from the general population;

· whether passengers who were asymptomatic during the isolation period later tested positive; and a myriad of other relevant questions that would allow us to more accurately project the Diamond Princess mortality rate onto the general population.

What We Want to Know

What we want to know is the current prevalence of the infection in a random sample of the general population and to repeat this exercise at regular time intervals to estimate the incidence of new infections. Sadly, due to the deficit of testing and the lag time between onset of illness and death, that information is lacking.

In the absence of data, we are left with estimates by comparison to other pandemics. A popular refrain is that the new coronavirus has a population-wide fatality rate higher than the < 1% of the seasonal influenza and lower than the 6-8% of the Spanish Flu here.

Cost Benefit Analysis

Value of A Statistical Life

When looking at risk/reward trade-offs that people make with regards to their health, economists often consider the value of a statistical life (VSL). The VSL is an estimate of willingness to pay for a reduction in mortality risks not the price someone would pay to avoid certain death.

By illustration: Suppose a large municipal hospital wants to purchase 1,000 ventilators at $25,000 each for its intensive care unit. The administrator of the hospital must conduct a cost/benefit analysis to determine if the $25 million cost of purchasing the ventilators is worth the benefit of saving 1,000 lives per year. Finally, let’s say that the local community is willing to pay $100 more in taxes a year to cover the cost of the ventilators. The VSL would be calculated in this manner: $100 [The increase in taxes per taxpayer] X 200,000 [The number of voting tax payers]/1,000 [the expected reduction in deaths from 1,000 to 0] = $20,000 per statistical life. $20 million dollars would be needed to save 1,000 statistical lives.

Knowing that the cost of saving 1,000 lives is worth $20 million dollars to the community now enables the hospital administrator to determine that it is not worth advising the local government to spend $25 million on the ventilators.

VSL estimates are used widely in the U.S. and other countries to consider the costs and benefits of environmental regulations, health, and safety. Estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Food and Drug Administration and Department of Transportation range from $7.9 million to $9.6 million for either one year of additional life or for the statistical value of a single life. here, here, here.

Calculating the dollar value on human life can help examine the cost-benefit trade-off of how much we should be willing to damage/support the economy to prevent the spread of Covid-19. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), if no actions were taken to prevent the spread of Covid-19, between 160 million and 214 million Americans would be infected, with between 200,000 to 1.7 million people dying from it. Using the VSL methodology, the older the average age of those killed by Covid-19, the lower the value of the statistical life. The lower the value of the statistical life, the less damage/support to the economy the government might want to accept.

If the average age of those killed by Covid-19 is 60, VSL puts the cost of each death at approximately $5 million. Using the CDC’s worst case estimate, the economic cost of American lives lost [$5 million X 1.7 million] = $8.5 trillion, equivalent to almost half the $20 trillion of gross domestic product of the U.S. here.

The loss of national income approach attempts to account for the lost productivity due to illness that the VSL approach does not.

Loss of National Income

The loss of national income is calculated by estimating the reductions in the size of the labor force and reduced productivity, increases in absenteeism as well as the result of individual and social measures that interrupt transmission, but disrupt economic activity.

The World Bank has found that a pandemic of the same severity as the 1918 influenza pandemic would reduce the global gross domestic product by about 5%. It further estimates that 60% of that reduction comes from the disruptive effects of avoiding infection here and here. Using this approach, the worst case economic costs of Covid -19 to the United States could be $1 trillion. The World Bank, however, further calculates that the estimated losses of lower-income countries are more negatively impacted than high-income countries, so 5% is likely to be too high.

Neither the VSL nor the loss of national income approach take into account the social contract that governments have with their citizens and residents.

What Should a Politician Do

Depending on the intensity of the interventions, a combination of measures could result in one of two basic scenarios. In the first scenario, the interventions slow down the spread of the infection but would not completely interrupt its spread. Demand on the healthcare system is reduced, while protecting those most at risk of severe disease. The pandemic is predicted to peak over a three to four-month period with a significant decrease by the fall.

In the second scenario, more intensive interventions interrupt transmission and reduce case numbers to low levels. However, depending upon when these interventions are relaxed, the risk of more cases rises. here

Given so much uncertainty, prepare-for-the-worst reasoning leads to extreme measures of social distancing and lockdowns. Unfortunately, we do not know exactly how well these measures will work. here. School closures, for example, may backfire if children socialize anyhow, or if school closure leads to children spending more time with susceptible elderly family members who might also be their babysitters. School closures may also diminish the chances of developing herd immunity in an age group that seems to be spared the serious effects of the disease.

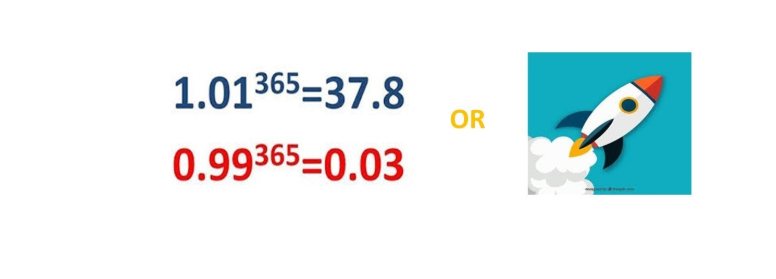

Both slowing the spread (scenario one) or suppressing the outbreak (scenario two) will require tremendous sacrifice. How does a country decide how much public health it can afford? President Trump recently tweeted “we can’t let the cure be worse than the problem itself.”

A variation of this same sentiment was heard when governments were considering options to the 2008 financial crisis. After more than a decade of extraordinarily loose monetary policy (the cure), the world economy has built up debt amounting to 230% of global GDP (the original problem was too much debt). The World Bank has warned that this last debt wave could dwarf the previous three. here

A miscalculation of the appropriate pandemic response combined with the financial fragility caused by the cure of the 2008 financial crisis has created the dual challenge of trying to save lives and livelihoods. Is it possible to create a public health response that both increases economic resiliency and reduces the risks of the pandemic?

To do so, a government should focus in the near term on redirecting all productive capacity to overcome the shortages of equipment and services required to respond effectively to the pandemic. In the mid-term, the government should be laser-focused on investing in pandemic prevention.

Values-based Assessment

Citizens, residents, and corporations fulfill their part of the social contract by paying taxes and following the law. The government honors its part of the contract by making sure its borders are safe and secure. Abandoning patients because they are old, or workers because they are in the gig economy, or corporates because they are small, especially in times of emergency, is a violation of that bargain.

If people and institutions cannot be sure that the government will protect them, they will substantially alter their behavior. And there is no formula that can estimate the worst-case scenario for a loss of global trust. #coronavirus #covid-19, #leadership #capitalism